Be good

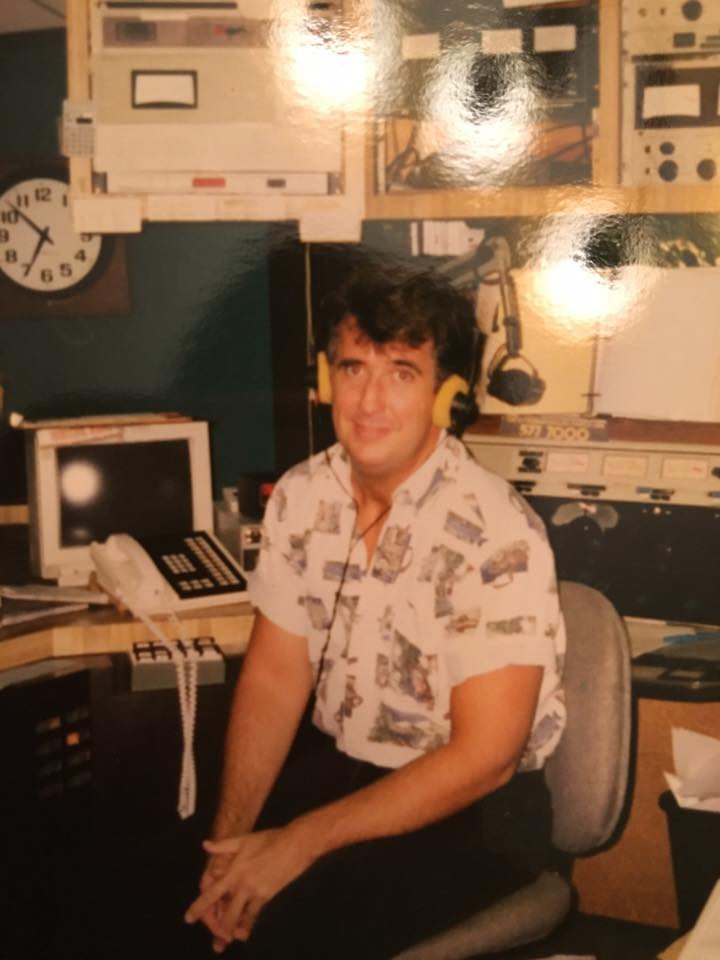

JohnStephensBurk

I noticed this over the past few months. Whenever someone would leave the room, my father would say, “Be good,” by way of parting. He did this with friends, family members, doctors and nursing staff. I thought it was an odd way to say goodbye, but I didn’t put the pieces together until earlier this week, as I received an outpouring of condolences, anecdotes, and information.

From the mid 1970s to the late 90s, my father was a radio personality. This was, to hear others talk, the golden age of radio. Back when you listened as much for the disc jockey as the music. I knew my father was beloved, even if years had passed since his voice was heard over radio waves, but I don’t think even I understood how much. Though he hated country music, he was best known for his twenty-year stint at a local, popular country music station. I shared his disdain for country, so I rarely listened to him. I’d catch him whenever I was at school, or in other public places, but I wasn’t a dedicated listener. And when you grow up knowing your dad is on radio, there is no novelty. You just accept it.

On Thursday, the night of the visitation, I listened to my father’s farewell address for the first time. It was emotional, difficult as hell, and my siblings and I were doing our best to not break down. The words he ended his career with were the same he closed each show with: “Be good to yourself and to someone else.”

Even years after he was off the radio, that remained important to him. “Be good,” he’d say to anyone leaving the hospital room.

My father was sick most of 2015. Up until 2015, we hadn’t had a particularly close relationship. He was a deeply emotional man, very loving and tender-hearted, but somewhat detached from the outside world. Describing my relationship with him was often difficult, because at the core, he was a very good man, if not a little short-sighted. He could be unintentionally hurtful by not showing up at something or not calling you. By the same token, he wanted to avoid conflict at all cost, because he didn’t know how to address it. Trying to express your feelings to him was often a futile effort, as it would only succeed in making him feel bad about himself and unable to fix it.

Still, the love between us, at sometimes strained and in itself difficult, was very deep. So when Dad was diagnosed with lymphoma on April 1, 2015, I immediately made myself available to him. The next few months were a series of tests, appointments, and two lengthy hospital stays. He also had numerous day-long chemo stints, most of which I attended in full, or at least in part. I took him to Barnes in St. Louis for a biopsy in November, and was planning to take him back on Friday for the second round of his clinical trial.

Instead, I attended his memorial service.

Losing Dad has been intense and painful. In the week since he passed, I’ve done several things to channel my grief. I wrote his obituary, something I didn’t know I could do until my stepmom told me he would have wanted me to. I also wrote him a letter, am in the process of fundraising a park bench in his honor, and am planning a trip with my brother, older sister and our spouses to lay Dad to final rest at Wrigley Field.

All of this would’ve been so much more difficult had Dad and I not bonded in 2015. Had whatever had been wrong between us not been healed. We spent more time together over the course of his illness than we had, I think, in the last 10 years. He came to trust and rely on me in ways he never had before. Two weeks before he died, he and I were sitting in his hospital room, talking. He teared up at one point and said, “I’ve been a bad father.” I took his hand and kissed his head and told him whatever anger I’d had for the past was over, and he’d been forgiven.

Last Saturday, the last words he spoke to me were, “I love you.”

The last thing he called me was “his special angel.”

Not everyone gets that. I am so fortunate that I did. I’m fortunate that the regrets I have now are minimal. There are other things I wish I’d told him, of course, but we were given a remarkable opportunity, and we seized it. That makes the loss a bit more bearable.

I wrote the bulk of Sinners & Saints #5 in November as part of NaNoWriMo. 2015 proved to be a shitty year to try and write, with all the cancer stuff, but I had managed around 12k before NaNo kicked off. In the meantime, I outlined and planned. My hero, Campbell, I knew was going to be representative of my anxiety disorder. I knew writing him would be difficult, because what he’s going through in the book is so completely reflective of me. I’d never written a character as closely based on me as Campbell—but anxiety is so misunderstood, I felt it had to be touched upon. I wanted to show someone who is a prisoner of his own mind, yet still strong and, for all intents and purposes, normal. Campbell was that vehicle.

After Dad got sick, I decided to make the book even more autobiographical by giving the heroine a recently deceased, somewhat estranged father, as well as a step family with whom she has a tense relationship. Before Dad passed, I was nearly 70k into it the book, and I’m faced now with completing the book on the other side. Now I’ve actually gone through what my character is going through—but unlike her, I received closure. One of the things I was initially exploring with her character was how to address a death of someone you love deeply, but who died before you could make peace with whatever was wrong with your relationship.

The book was always Dad’s. It contains some of the rawest scenes I’ve ever written, and I have to finish it now. I think it’ll be therapeutic, but very difficult. Like writing his obituary, and the letter I penned a few days ago. But I know it’ll be my favorite of my books when it’s finished because there is so much me in it. Because it’ll always be the book I wrote when Dad was sick, when Dad was dying, and after Dad was gone.

That’s where I am now. And where I’ll be later today when I start writing again.

Unsurprisingly, I’ve been thinking a lot about death this week. How hard it is on those left behind, on how you’re never prepared for it, even after months of caring for someone. How large a hole a person can leave in your life. I have fewer regrets now than I would have, but I still have regrets. I don’t know if you can ever be assured there won’t be regrets, because I’ve asked myself that a lot over the past few months—if Dad were to leave, would I be at peace. I thought the answer was yes, but there’s always something. Something you don’t consider until it’s too late.

We all hear it—hug your loved ones now. Tell them you love them. Regrets might not be eliminated, but they can be reduced. I’ll add this: be good to yourself and to someone else. It’s a simple philosophy, but a beautiful one, and I’m going to go forward each day with it in mind.